Last week I gave a short talk on the Danish 19th century philosopher and priest N.F.S. Grundtvig at the Danish Embassy in London in connection with the launch of the new Danish school Dania*. And I thought that other people might be interested in the topic: “Grundtvig and Education”**.

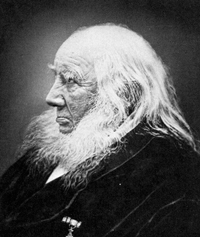

Nikolaj Frederik Severin Grundtvig, or just Grundtvig, was born on September 8, 1783 and died on September 2, 1872. Though he spent considerable parts of his life outside the capital, he is associated with Copenhagen where he would often be seen walking the streets. Important contemporary Danes are: Søren Kierkegaard and Hans Christian Andersen. This portrait by C.A. Jensen is from 1843

Before I even begin, I need to emphasise that Grundtvig was a complex character who lived in a complex time: born at the end of the Enlightenment he came of age in the Romantic period, which saw Denmark reduced from a prosperous European naval power to a marginal country without much influence. He also witnessed, however, the birth of the Danish democracy, the rise of the people as a political entity and the development of the notion of nationality.

Grundtvig is best known today for being the ideological father of the Danish folk high-schools (for more information on modern folk high-schools: http://www.danishfolkhighschools.com/), but other prominent followers are Christian Flor, who founded the first folk high-school in Rødding, and Christen Kold, who founded the first “friskole” (independent school) in Ryslinge in 1852.

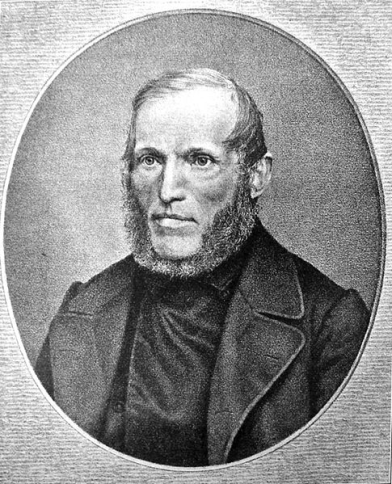

Christen Mikkelsen Kold (or Kresten Kold) was born on 29 March 1816 and died on 6 April 1870. Inspired by Grundtvig, and himself in opposition to the state school system, he was involved in the founding of many Danish independent schools and folk high-schools from the mid 19th century.

The Danish “folkeskole” (the people’s school) is normally said to begin with the school reform of 1814 which introduced schooling for everybody for 7 years, but only in 1855 did it become legal to establish private schools and in 1899 they began receiving government funding (today the state pays 70% of the costs of private schools, which means you can send your child to a private school for around £150/month). But why did Grundtvig, and people like Kold, feel the need to establish private schools?

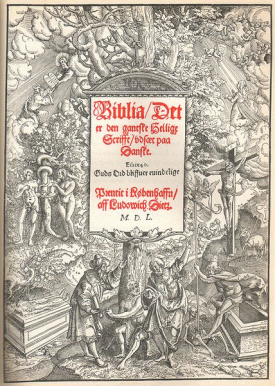

We first have to go back in time, back to the Reformation in 1536. One of the key ideas was that everybody should be able to read the Bible, which meant that it was translated from Latin into all the European languages (the first complete translation into Danish is from 1550 and is called “the Bible of Christian III”).

This meant that people had to learn how to read – but the idea was not to enlighten people in a general way, and school was never an individual process but served this very specific purpose, namely being able to read the Bible. Knowledge – unchallenged – was handed down from the teacher (i.e. the priest) to the pupils.

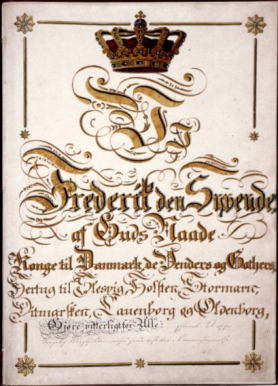

If we then jump forward to the 1830s and 1840s, there was political unrest all over Europe, and the ruling classes were scared to death by the idea that the people wanted political power. Denmark got its first constitution in 1849 without any bloodshed, but it was not clear what democracy was to mean: the national-liberals, on the one hand, wanted a democracy led by a small, well-educated elite; Grundtvig, who was very sceptical of democracy – something which I will not explore further here – championed, on the other hand, the education of the people to make them capable of functioning in a democracy.

With that brief historic overview in mind, let me turn to Grundtvig’s ideas on education. Grundtvig did not see learning as the real purpose of education; the goal was rather the awareness and cultivation of human nature. Humans, created by God in his own image, were endowed by a spirit, which, according to Grundtvig, was first and foremost expressed through the living word (this based on Luther’s ideas). In this way, man is or becomes part of a community, for instance the Danish or the English community (and I should mention here that Grundtvig was not just national, he was also very interested in and championed Nordic cooperation, suggesting the creation of a Nordic university in Gothenburg. He was also interested in Old English poetry, and in 1820, using a Latin translation, he published the first translation of Beowulf into a modern language). To understand this community and to understand oneself as a part of it, Grundtvig argued that we have to turn to history, both national and international, and literature. Neither is revolutionary: literature and history have always been used to understand the present; it is the focus on the individual development that is new.

And these ideals have influenced Danish schools right up to our time, the idea being that schools should emphasize the narrative and dialogical way of teaching with their inherent respect for individuality, and abandon the old system of rote learning or learning by heart. This might not sound radical today, but it was a whole new way of thinking about the individual and about learning: the emphasis was on the student and on developing as a person; it was a movement away from focusing on the teacher whose job it was to fill the empty vessels, the students, to seeing students as individuals whose paths to insight were different, and this is one of the pillars of the modern Danish school: that students must be met on their own level, must be part of their own learning. This means, for instance, that Denmark does not really have a fixed national curriculum. Danish teachers can also teach in their own way, using their own methods, and they are only required to follow few national rules and regulations (such as the teaching of certain canonical writers and certain historic periods such as the Viking age).

Another very concrete outcome of this philosophy is that tests and exams do not play crucial parts in Denmark. Most pupils begin getting grades from year 8, and after year 9 (technically year 9 and 10 as there is also a reception class “year 0”), the end of the Danish “Folkeskole”, most will sit exams. These are, however, not even mandatory, and some schools use neither grades nor exams.

I will let Grundtvig himself end this rather long blog, which could have gone on much longer, and personally I think his words are important to remember in today’s world where everything seems to be about competitiveness, productivity and materialism:

”Phantasie og Følelse hører ligesaavel til et ordentligt Menneske som Forstand”

(Imagination and feeling are as much a part of a well-rounded individual as intellect)

Notes:

* I have no stake in the Dania school and the content of this blog is entirely my own.

**Trying to write a short blog-post about Grundtvig is slightly masochistic, akin to asking to be hit on the head with an academic sledge hammer. I am, in all fairness, no Grundtvig expert and all views presented in this blog are not the outcome of in-depth research but are meant as a mostly descriptive introduction to an iconic Danish philosopher. For further information, I suggest looking at http://grundtvigcenteret.au.dk/. If any experts out there have any comments or suggestions, please send them to me and I will be happy to integrate them into my blog.

Danish Review 2013 / 2014: Translation, food, politics, music, literature and much more

Thanks Jesper, that was a fascinating presentation on Grundtvig and how his teaching is incorporated into Danish Schools now. It was very well delivered. I very much enjoyed listening to your talk.

Kind regards,

Mike Papesch

Trustee Dania School